When I search for a donor, I look for something of myself in her, but I've never understood why. What's the point? Am I trying to fool myself?

I've been asking myself these questions for weeks, thinking that they were rhetorical, and then the other day I realized that they aren't rhetorical. That the answer is Yes. I am trying to fool myself. I am actually searching for a donor who looks enough like me so that my babies might let me forget that we aren't genetically related.

Never mind how this could possibly work. Why would I do this? It's an awful lot of trouble to go through when the tricker and the trickee are the same person. I threw out a bunch of different possibilities, and when I started crying, I knew I'd discovered the reason:

It's not the loss of my genes. It's the death of my heritage.

I'm a first generation American and the product of a lineage whose survival was doubtful. My parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents have stories of hunger, discrimination, persecution, flight, and death. I've heard these tales over and over again, told to me in third world accents during turmeric-spiced dinners - descriptions of where my grandmother laid the beds in their 2 bedroom apartment to accommodate 10 children, and how my aunt's fingers were broken when she was 8 because she tried to learn to write her name.

And the story of my father who had one set of clothes growing up: a pair of pajamas that he both slept and went to school in. When enough time had passed, and they were finally too small and torn in equal parts, my dad was so excited to be getting something new - not because of the updated wardrobe, but because then his mom would take his old pjs, wrap them up in twine, and give it to him so he'd have a ball to play with.

These stories of endurance are the stories of my blood, and my blood won't be passed on to my kids. The loss of all this history is too profound for me to swallow right now, and I'm just not yet ready to bury my grandparents lineage. What this means is that I'm committed to selecting a donor who can help me pretend this isn't happening. I'm going ahead with the charade, and I'm looking for an ally in my self-deception.

After several days of toggling between profiles of brown-skinned, black-haired women, a new donor came up. She's from my family's part of the world, and there's something about her that reminds me of my father's mother, of my mother's sister, and of me. She could work.

If we conspire together, this woman's genetic babies and I could nurse the sham for a little longer. I know that more time, more tears, and more therapy will help me accept that my children won't have my past in them, but I can't think about that right now. I'm too busy creating a future where early on Sunday mornings, when eyes like my grandmother's look back at me, I might be able to snooze for 5 more minutes before waking up.

My eggs don't work, so I've manifested a baby via egg donation. Let's blog and see what happens.

Monday, February 27, 2012

Saturday, February 18, 2012

Losing Las Vegas

Our second donor fell through.

Turns out she's a flake. It took her an eternity to fill out the paperwork, but we let it pass because she apologized profusely and convinced us that she was a changed person. Now she's gone a week without responding to any phone calls, emails, or texts. Sigh.

N says we shouldn't have trusted a woman from Las Vegas who dresses like a stripper. I suppose he has a point, but it doesn't make this any easier. I bonded to her. I mean, she asked to see our photo; I thought that was a sign she was committed. It wasn't.

OK, added to my criteria: someone who looks like she can keep her clothes on.

In the meantime, I'm really, really bummed.

Turns out she's a flake. It took her an eternity to fill out the paperwork, but we let it pass because she apologized profusely and convinced us that she was a changed person. Now she's gone a week without responding to any phone calls, emails, or texts. Sigh.

N says we shouldn't have trusted a woman from Las Vegas who dresses like a stripper. I suppose he has a point, but it doesn't make this any easier. I bonded to her. I mean, she asked to see our photo; I thought that was a sign she was committed. It wasn't.

OK, added to my criteria: someone who looks like she can keep her clothes on.

In the meantime, I'm really, really bummed.

Friday, February 10, 2012

Will the Real Mom Please Stand Up?

At some point, someone will ask me the single most upsetting question about my future kid's donor:

We live in a culture where the definition of the "real parents" is in flux. It's traditionally understood that real parents are the people who you look like, and it takes a certain amount of work to undo that conditioning. In the meantime, insensitive comments like these make DE parents a tad upset.

For example, donor egg moms really, really, really don't like when egg donors are referred to as mothers of any sort, and phrases like "genetic mothers" can send folks into a tizzy. What they're reacting to makes sense, mind you. It's threatening to feel disconnected from your DE child (which is bound to happen because parent-child relationships are nuanced), and it's threatening to have your bond with your DE child devalued by people around you (which is bound to happen because people are idiots). In context, these moms' reactions are completely and entirely appropriate.

What I struggle with is that DE moms defend their legitimacy by saying things like "I carried him," "I gave birth to him," and other assertions of biological involvement. I get what they mean, but this argument makes me uncomfortable because it implies that mothers who didn't give birth to their children aren't as worthy of the "mom" title and - the inverse - that birthmothers and surrogates are. All of which is to say that I think pregnancy a flawed defense of motherhood, and my opinion is that we shouldn't use it.

As a community, our tact should be different. It's simply a matter of reinforcing what we know to be true: real parents are the parents who raise the children.

This approach is particularly important when we consider that we're a part of a broader community of women, men, and couples who've turned to donor eggs, donor sperm, surrogates, and adoption to help us complete our homes. Defining parenthood is a collective concern, and we should do it in a way that is as inclusive as possible of these diverse family make-ups.

Personally, (as I've mentioned before) I don't feel threatened by having my donor referred to as the genetic mother. She is the genetic mother, and I'm the biological mother. That's the situation, and I'm not afraid to name it.

The problem would be if you say anything about her being the real mother, at which point I'm also not afraid to mother-fuck you up.

Do you ever wonder about the real mom?Obviously the person asking will either be an idiot or an asshole, but either way I'll know what they're thinking, and that's precisely the problem.

We live in a culture where the definition of the "real parents" is in flux. It's traditionally understood that real parents are the people who you look like, and it takes a certain amount of work to undo that conditioning. In the meantime, insensitive comments like these make DE parents a tad upset.

For example, donor egg moms really, really, really don't like when egg donors are referred to as mothers of any sort, and phrases like "genetic mothers" can send folks into a tizzy. What they're reacting to makes sense, mind you. It's threatening to feel disconnected from your DE child (which is bound to happen because parent-child relationships are nuanced), and it's threatening to have your bond with your DE child devalued by people around you (which is bound to happen because people are idiots). In context, these moms' reactions are completely and entirely appropriate.

What I struggle with is that DE moms defend their legitimacy by saying things like "I carried him," "I gave birth to him," and other assertions of biological involvement. I get what they mean, but this argument makes me uncomfortable because it implies that mothers who didn't give birth to their children aren't as worthy of the "mom" title and - the inverse - that birthmothers and surrogates are. All of which is to say that I think pregnancy a flawed defense of motherhood, and my opinion is that we shouldn't use it.

As a community, our tact should be different. It's simply a matter of reinforcing what we know to be true: real parents are the parents who raise the children.

This approach is particularly important when we consider that we're a part of a broader community of women, men, and couples who've turned to donor eggs, donor sperm, surrogates, and adoption to help us complete our homes. Defining parenthood is a collective concern, and we should do it in a way that is as inclusive as possible of these diverse family make-ups.

Personally, (as I've mentioned before) I don't feel threatened by having my donor referred to as the genetic mother. She is the genetic mother, and I'm the biological mother. That's the situation, and I'm not afraid to name it.

The problem would be if you say anything about her being the real mother, at which point I'm also not afraid to mother-fuck you up.

Labels:

egg donation,

infertility,

language,

My Head

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Bio. Genetics.

After searching, downloading, and listening to every single NPR segment about egg and sperm donation they had, something occurred to me:

Women who use DS to conceive call their donors biological fathers.

Women who use DE to conceive never call their donors biological mothers. Ever.

This made me think about the words "biology," "genetics," and "biogenetics" and how this language reflects the reproductive roles of women and men.

To review how men make babies: they have sex (biology) and deposit sperm inside the woman (genetics). That's it. Their entire biogenetic function is tied to a single act that takes a few minutes. (Yes, boys, I said a few minutes).

For women, it's different. Women make babies through ovulation (genetic) but also through 9 months of gestation, 12-24 hours of labor, and another year of nursing (biology). So unlike men where the biogenetic experience is singular, women can actually separate out those two parts so that there are unique biological and genetic experiences in the baby-making process.

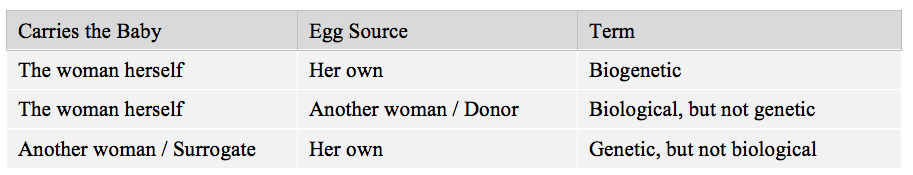

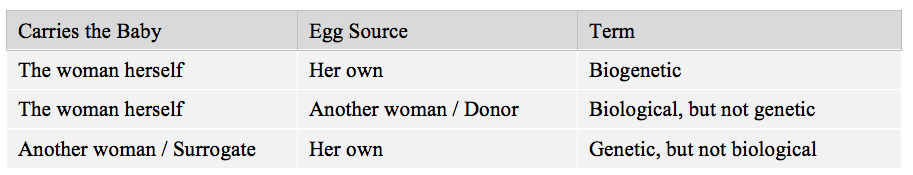

The implications of reproductive function on the language is the following (yes, it's another chart).

Again, I just make this shit up as I go along, but I think it sounds good.

Even though I'm convinced of these words' proper usages, I've caught myself mixing them up; I sometimes say that my kid won't be biologically mine when what I mean is genetic. I know why I slip up: it's because this whole thing is some crazy sci-fi shit, and it's not easy to wrap my head around.

The silver lining, though, is that it'll be confusing for others, and I'll get to mess with them by introducing conversations about the linguistic implications of reproductive technologies and their effects on popular understandings of biogenetics.

That'll be fun.

Women who use DS to conceive call their donors biological fathers.

Women who use DE to conceive never call their donors biological mothers. Ever.

This made me think about the words "biology," "genetics," and "biogenetics" and how this language reflects the reproductive roles of women and men.

To review how men make babies: they have sex (biology) and deposit sperm inside the woman (genetics). That's it. Their entire biogenetic function is tied to a single act that takes a few minutes. (Yes, boys, I said a few minutes).

For women, it's different. Women make babies through ovulation (genetic) but also through 9 months of gestation, 12-24 hours of labor, and another year of nursing (biology). So unlike men where the biogenetic experience is singular, women can actually separate out those two parts so that there are unique biological and genetic experiences in the baby-making process.

The implications of reproductive function on the language is the following (yes, it's another chart).

Again, I just make this shit up as I go along, but I think it sounds good.

Even though I'm convinced of these words' proper usages, I've caught myself mixing them up; I sometimes say that my kid won't be biologically mine when what I mean is genetic. I know why I slip up: it's because this whole thing is some crazy sci-fi shit, and it's not easy to wrap my head around.

The silver lining, though, is that it'll be confusing for others, and I'll get to mess with them by introducing conversations about the linguistic implications of reproductive technologies and their effects on popular understandings of biogenetics.

That'll be fun.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)