Everyone is telling me that using an egg donor for my IVF is almost no different from using my own egg. Their arguments go like this:

Friends: You're going to be the one to carry it for 9 months.

Doctor: It's just a genetic seed.

Scientist father-in-law: Current research shows that the embryonic environment is just as influential as genetics.

Husband: Uh...

Of all these, it's my husband who has the most insightful line of thinking because the truth is that, while there's validity to what the others are saying, the reality of egg donation is more complicated than that.

Part of the complexity is that the experience varies for each person dealing with it. For some people involved, it's closer to a natural conception, but for others, I think it's more like adoption.

To describe what I mean, I drew a continuum and plotted each player on the line: the mother, the father, the donor, and the kid.

To answer your questions in advance,

1) Yes, this is an odd thing to do.

2) No, I don't have any personal experience with any of this.

3) Yes, I'm just making this up as I go along.

OK, here goes.

For the father, having a child via egg donation isn't too different from own-egg IVF - assuming it's his sperm, that is. His wife is pregnant, and his parents' genetic lines are wholly represented in the kid. Yes, he lives in an egg donor home, but his genetic relationship to the kid is entirely traditional. Thus he's furthest on left.

For the donor, she's just aiding a couple who is having trouble conceiving, and it's a strictly medical procedure. The donor experiences no pregnancy, no labor, and no delivery, and she doesn't place a baby in another person's home, so the process is obviously very different from a birthmother's. On the other hand, she knows that the resulting children will be genetically hers. Throughout her life, she will wonder about them, and even though there won't be an emotional bond, curiosity will tickle just like it would for a birthmother. Because of all this, I've put her on the left, although not as far over as Pops.

For the child, the emotional experience will fall closer to the middle. Yes, his mother carried him, delivered him, and nursed him, but he won't remember any of that. All he knows is that he's genetically related to his father and not to his mother. Exactly how the kid will be affected by this depends on a million factors, but to some degree, when it comes to his mother, much of what he experiences will be similar to an adopted child: there will be a level of genetic loss, grief, and un-belonging. Near to the middle he goes.

For the mother, the experience really is a lot like adoption. After the pregnancy-delivery-nursing part is over, she'll have to face lots of the same things that adoptive moms do. Strangers will comment about how the kid looks nothing like her, and people will ask about the child's "real" mother. A bit of consolation is that her child is genetically related to his father, but that can also feel painful since Mom is the only one who can't experience that bond. For all these reasons, I'm putting her nearer to the right of the continuum.

Again, I've got no hard data to back this up, but I think it sounds really good.

During my philosophizing, I came to an epiphany, and while I don't like to wax feminist, I'm going to play the card: I think the reason this all gets whitewashed is that the boy doctors are running the show, and from the male perspective, it's not at all like adoption. As far as the docs are concerned, they're just swapping one egg for another. For the fathers, there's no genetic difference. And the egg donor's experience is supervised and contained by the doctor. It's understandable, then, why these folks view it the way they do.

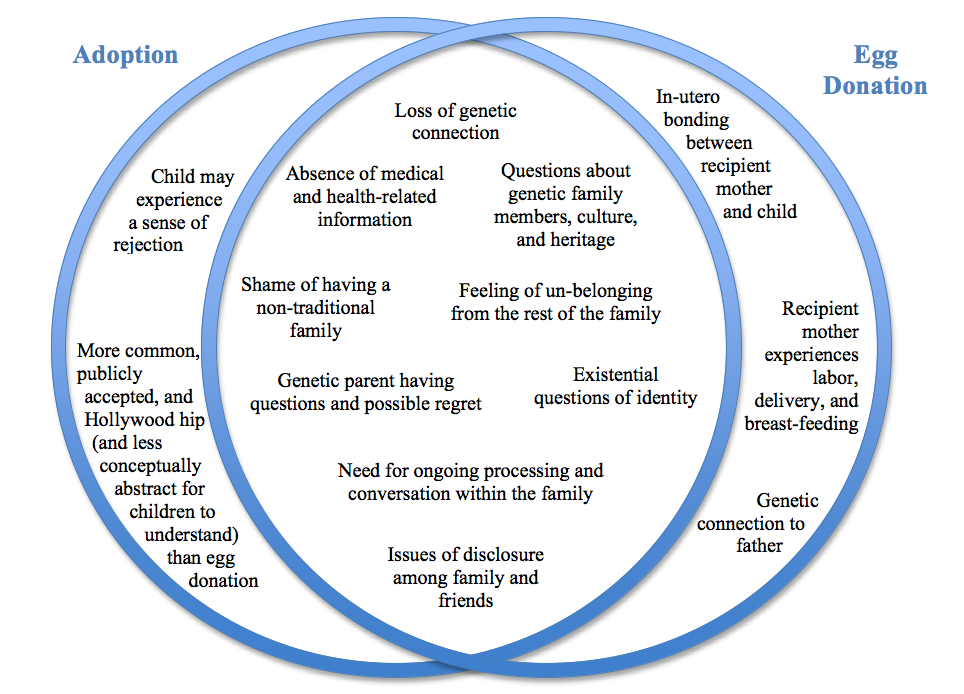

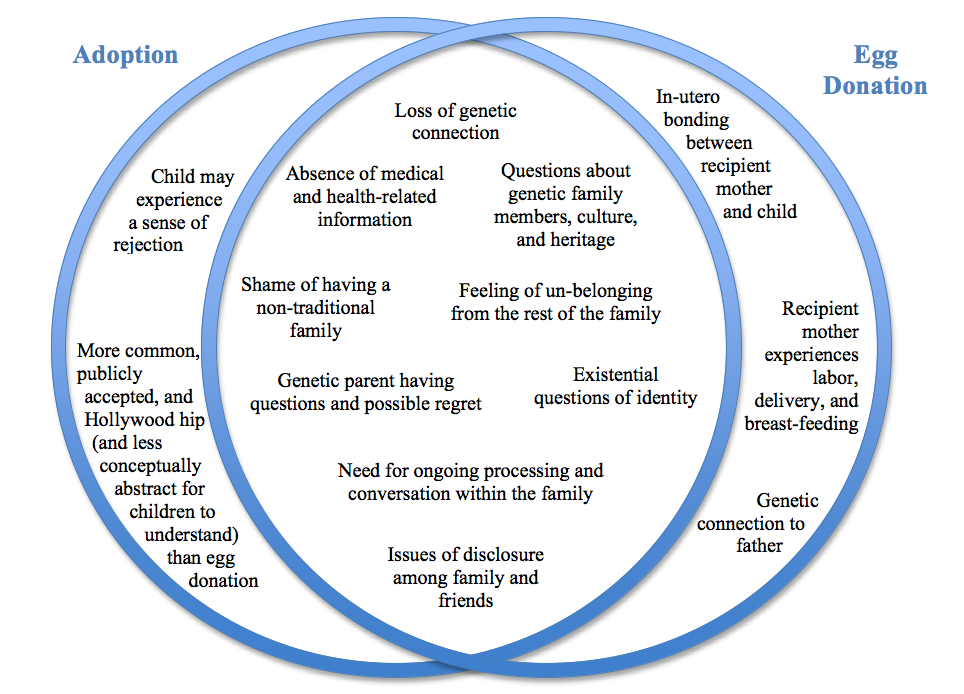

But for the mothers and children, egg donation has more psychological, social, and emotional similarities to adoption than to any other form of family building. To illustrate this further, I drew a venn diagram laying out the overlap. (Again, yes, I'm weird for doing this. Just go with it.)

Sure, there are distinctions, and yes, there's a lot missing, but I still maintain that no matter how complete this diagram gets, the similarities between egg donation and adoption are greater than the differences.

Ultimately, I think this is a linguistics issue. It's called an "egg donor procedure," and it produces an "egg donor baby," but this language places all the focus on the doctors and the donors. Yes,

she's donating, but I'm

receiving, and these phrases don't say anything about

my experience. Come to think of it, this woman isn't even donating; she's actually charging us several thousand dollars (which I think is fair considering all the time, effort, pain, and risks). In light of all this, I can't help but feel that "egg donation" is a misnomer.

This is an "egg adoption." Egg adoption is an all-around more accurate term, and calling it anything else undercuts the emotional, social, and practical realities of the mother-child relationship. If you ignore that egg adoption is philosophically truer, I think that will just make it harder in the future when the square peg doesn't fit into the round hole.

I need to think of this as egg adoption so I can prepare myself for what I might face when raising a child that isn't genetically related to me. The adoption community has worked hard to create a culture of openness, integrity, and normalcy, and it has a deep understanding of the social and psychological implications of the process. It's obviously not exactly the same, but I'd be crazy not to learn from them if I'm going to consider this.

Yup. I said it. I'm considering this.

Weird.